22nd November 2017

I’ve been researching undercover policing ever since the boyfriend I knew as Mark Cassidy left me in spring 2000. Like the other female activists bringing cases of undercover police abuse to light, I have become skilled in scouring documents, interrogating and interpreting evidence. We’ve fought a legal case against the Metropolitan police to expose its institutional sexist practices, and waited for five years for an apology that should have been given much earlier.

Now I’m one of the 180 “non-state core participants” (NSCPs) in the public inquiry into undercover policing. Established in March 2015, the inquiry was due to report in July 2018, but it’s looking unlikely any evidence will be heard until 2019, and the end date is no longer even in sight.

Sir John Mitting, the inquiry chair, is sitting for three days this week in the Royal Courts of Justice in London, listening to legal arguments and counter-arguments about police anonymity. He obliquely responded to a letter from October signed by 115 NSCPs expressing our concern about the inquiry’s lack of openness and transparency, stating that his priority was to “discover the truth”.

For many of the ordinary people attending as core participants, the Royal Courts building – with its endless gothic corridors – is intimidating and alien.

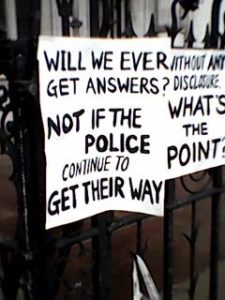

Sitting in the public gallery of court 76 is a collection of journalists, core participants, and our friends and family. We are listening to the lawyers discuss principles established in case law that very few of us sitting at the back will understand. We usually sit politely and wait in good faith, as we’ve been doing now for two years, for crumbs of information about the police officers who collectively used and abused us. But yesterday morning was different. Vocal interventions from core participants expressed our frustration at a process which, despite the judge’s reassurance, is looking more likely to obfuscate than reveal the truth.

Because nothing is being revealed. Not even the full list of the groups spied on. Despite the Metropolitan police apology issued to me and the other women, Mark Jenner (who I knew as Mark Cassidy) is the only officer cited in our case whose identity has still not been officially confirmed by either the Met or the inquiry. No reason has been given. The latest tranche of documents promised that some names would be revealed: a few cover names (including HN81, who infiltrated the Stephen Lawrence family campaign) and some real names. Each officer is coded by an HN number, and the list is dizzying.

Because nothing is being revealed. Not even the full list of the groups spied on. Despite the Metropolitan police apology issued to me and the other women, Mark Jenner (who I knew as Mark Cassidy) is the only officer cited in our case whose identity has still not been officially confirmed by either the Met or the inquiry. No reason has been given. The latest tranche of documents promised that some names would be revealed: a few cover names (including HN81, who infiltrated the Stephen Lawrence family campaign) and some real names. Each officer is coded by an HN number, and the list is dizzying.

But many officers we will learn nothing about. The judge has already made some orders for some evidence to be heard in secret, and it will no doubt be so heavily redacted before it reaches the public as to be meaningless.

In these cases, he will rely on information collected by the police about their own officers. How can this be fair? How can a judge determine the impact of secret deployments if those who were targeted are not told who spied on them?

In these cases, he will rely on information collected by the police about their own officers. How can this be fair? How can a judge determine the impact of secret deployments if those who were targeted are not told who spied on them?

Without transparency, how do we know if these nameless HN numbers infiltrated other family justice campaigns? How do we know if they had abusive, intimate relationships with those they spied on? How do we know if they passed on information to private corporations resulting in trade unionists being blacklisted from work? And how do we know if they acted within the law?

Trying to access and make sense of their redacted evidence buried deep within the inquiry’s website is hugely challenging. Like the corridors of the building, the complexity of the website renders many of us bewildered and disengaged from a process in which our participation feels anything but “core”.

Despite institutional racism being central to the setting up of the inquiry, when it was revealed that the Lawrence family was spied upon, the inquiry team is all white. It is predominantly male and is now being chaired by a judge who is a member of the men-only Garrick Club. A letter sent to the home secretary in September, requesting a meeting to discuss the inappropriateness of the new judge, has been ignored.

Instead of recognising the damage done to those of us who tracked down our ex-partners, various witnesses are characterising our searches as malicious. And the emphasis the police are placing on the right of the abusers to protect their families contrasts sickeningly with their total lack of regard for the families they intruded upon.

Mitting must appreciate the context in which his inquiry is now taking place. Since the recent revelations about abuse of women by men in the film industry, parliament and elsewhere, the misogyny of our society has become unignorable. What happened to us was sustained abuse.

The men who have been exposed in other spheres have been named and shamed. Harvey Weinstein, Max Stafford-Clark and Kevin Spacey cannot hide who they were when they were abusing their positions of power.

Sexual abusers should not be able to rely on a court anonymity order

Undercover police officers, by contrast, were given state-sponsored identities. From what we know thus far, it’s likely that many committed long-term and far-reaching human rights abuses, for which they may never be held publicly responsible if their real names are concealed. If they didn’t commit these wrongdoings, what are they afraid of? If their targets were legitimate, why do they need to hide behind fake names? Sexual abusers should not be able to rely on a court anonymity order. No one else alleged to have committed such abuse is offered this privilege.

We know that three officers who had intimate, sexual relationships with activists (John Dines, Bob Lambert and Andy Coles) all went on to reinvent themselves, taking on public roles as advisers and consultants to international police departments and university criminology courses, or holding public office as a deputy police and crime commissioner.

Without knowing the real names of the officers involved in our lives and the lives of others, how do we hold to account those who have since created illustrious careers advising policymakers on police matters? Many of us feel this inquiry is turning into another attempt at an establishment cover-up. Our patience is running out.

Without knowing the real names of the officers involved in our lives and the lives of others, how do we hold to account those who have since created illustrious careers advising policymakers on police matters? Many of us feel this inquiry is turning into another attempt at an establishment cover-up. Our patience is running out.

• Alison is one of eight women who successfully took legal action against the Metropolitan police over the conduct of undercover officers. Most of the women have chosen to remain anonymous. This piece was published in the Guardian newspaper on 21 November 2017.